“Do as I say, not as I do”. This was the phrase that Senator Tereza Cristina published on her digital media, commenting on the fact that the European Commission has postponed the obligation for European farmers to keep 4% of their land “non-productive”, i.e. preserved or fallow, as well as the relaxation and exemption of its farmers from various other environmental requirements.

The European Commission has officially adopted the “Common Agricultural Policy rules” granting exemption for European farmers from the conditionality rule on land lying fallow. The regulation, which entered into force on February 14, 2024, will apply retroactively from January 1 for one year, i.e. until December 31, 2024.

The partial exemption responds to various requests for greater flexibility from the bloc’s member states in order to better respond to the challenges and dissatisfaction of the EU’s own rural producers.

The bloc that is delaying local environmental protection is the same one that approved the European Union Regulation for Deforestation Free Products (EUDR) in June 2023. The EUDR requires assessment and proof that various agricultural products imported by the EU are not linked to deforestation.

As a result of this regulation, trade flows of meat, cocoa, coffee, timber, rubber, leather, palm oil and soybeans destined for the European bloc will have to prove their origin by sending geolocalized data of each shipment and carrying out due diligence in advance.

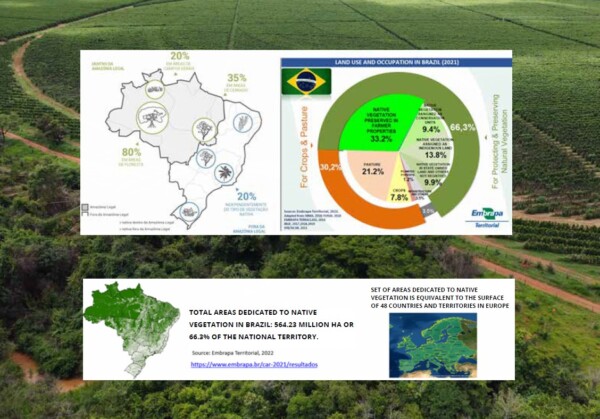

In this context, Brazil, the world’s largest net food exporter, a continental and diverse country with regions at different stages of development, has strict rules that require farmers to protect 20% of their rural property in the Atlantic Forest, 35% in the Cerrado and 80% in the Amazon.

In reality, these percentages are even higher, since international pressure has limited the legal suppression of vegetation, even though legal deforestation is a constitutional right of land use and is guaranteed by the Brazilian Forest Code, one of the strictest environmental laws in the world.

According to the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa), the total area dedicated to the protection of native vegetation in Brazil represents 564.24 million hectares, or 66.3% of the national territory. Of this total, 33.2% is preserved within rural properties! What’s more, the total area dedicated to native vegetation in Brazil is equivalent to the surface area of 48 countries and territories in Europe!

In this sense, the decision of the European bloc, the largest trade group today, is a mechanism of protectionism and trade barriers that does not respect the legislation of each country and therefore deserves to be strongly questioned by the World Trade Organization (WTO).

In challenging geopolitical times, multilateralism and trade agreements strengthen world trade and help mitigate the effects of economic crises.

The promotion of multilateralism fosters international trade with social inclusion, respecting the investments, projects and concrete sustainability activities underway in Brazil. Unilateralism and the adoption of trade barriers, such as the European Union’s EUDR, could jeopardize decades of progress in social inclusion and environmental protection.

One example is the social importance of the Brazilian coffee industry. Brazil has exemplary labor laws that focus on worker health and safety.

In addition, coffee promotes social inclusion, as the region’s Municipal Human Development Index (MHDI) – which measures income, schooling and life expectancy – is higher where the activity is present, and environmental protection levels are higher than required by law (Brazilian Forest Code).

For example, in Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo, the two main coffee-producing states, there is a very positive correlation between the area under coffee cultivation and the MHDI. It can therefore be concluded that the widespread consumption of Brazilian coffee around the world is a driver of progress and human development in the country’s producing regions.

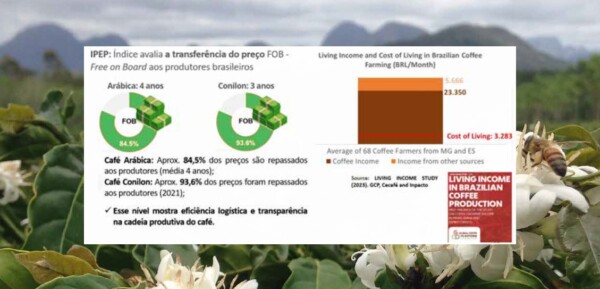

Cecafé has been regularly calculating and publishing the Producer Export Participation Index (IPEP) for almost two decades. Its aim is to estimate the share of Arabica and Robusta coffee producers in the value of goods cleared for export, the so-called Free on Board (FOB) value.

The Producer Export Participation Index has been close to 84.5% for Arabica and 93.6% for Conilon, with rare variations in the range. Compared to all other coffee producer nations, Brazil is the country where coffee exports transfer the largest portion of the FOB value to the domestic prices received by the producer.

Marcos Matos

CECAFÉ CEO

Leave A Comment